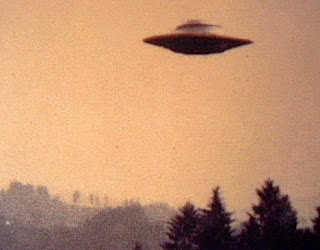

Let's discuss the two most likely sources of noise we are likely to encounter.

HIGH ISO NOISE

When we went and set the ISO to 3200, we knew we were in trouble. We went there because we had no choice. Given the poor light, we couldn't possibly hope to get a high enough shutter speed or a small enough aperture to freeze the action, compensate for the telephoto shake, get all parts of the room in focus etc etc. We knew that we were going to have to accept some compromises with noise in order to get the shot but there was something ABOUT the pic which was more important than the potential noise problem. If we went to the trouble of hiking up the ISO, we will probably feel that the image is important enough for some heroic efforts towards optimisation.

UNDEREXPOSURE

Even at civilised ISO settings, we can still get into noise trouble. Often we find ourselves having underexposed a relatively important image on a paying shoot which then has to have substantial mid-tone boosting - a perfect recipe for noise. If I have bracketted or gotten other, better exposed versions of the same subject I'll discard the pic in question but sometimes Sod's Law applies and it's all I've got. I then have to try to do something acceptable with it.

In either situation, we are going to have to accept that the noisy image will never be the impeccably smooth and colour precise object of beauty it MAY have been at low ISO settings and/or if we'd have exposed the thing correctly. What then are we to do?

- We can accept the noise as it is.

- We can make the noise seem more acceptable.

- We can try to reduce the noise.

- We can try to eliminate the noise

Certainly our decision making will be influenced by the ultimate display application. If the image will finish up as a small print or a relatively small image on a website, we enjoy a little more latitude than if it is to be published in the print media or blown up for framing. Likewise, depending on its subject value, a news pic will sometimes be acceptable in grainy greyscale but a commercial image in a display ad must be as technically perfect as possible.

Let's get one thing straight. With very few exceptions, noisy, high ISO images will RARELY be converted to clean, sharp, high detail images with one, simple, carefree pass of the NR software. It never really works that way. When we set out to remove noise artifacts, inevitably some details and texture will be interpretted as noise and get removed as part of the deal. In the final analysis, we WILL have to accept one or other of the above compromises ..... albeit, only after a good fight. For the purpose of THIS exercise let us decide to reduce noise to roughly acceptable levels - suitable for small prints and medium sized website illustrations

Until recently running "Noise Ninja" or "Neat Image" as a plug-in was the way to go. In recent times Photoshop and Elements have had the benefit of a serviceable noise reduction facility of their own in the form of Filter - Noise - Reduce Noise. Neat Image & co. are more powerful but with the judicious use of Layers and multiple passes on selected areas it can do pretty well.

Here is an approach upon which you may like to base your own experiments:

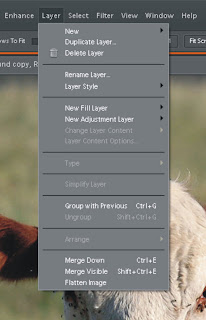

- Go to Layers menu and click on Duplicate Layer

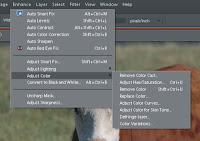

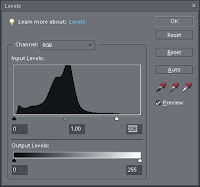

- Go to Filter - Noise - Reduce Noise. Strength 10, Preserve Details 20% and Reduce Colour Noise 70% Click OK

- Choose shadow areas and expanses of featureless open space (e.g. sky & walls) which continue to show noise, select them roughly with the Quick Selection tool. Re-run Reduce Noise on the selected areas with the previous settings.

- Tour the image, viewing it at 1:1 (100%) and using the "Blur Tool", tidy up any last remaining spots of noticeable noise or processing artifacts

- Run the Unsharp Mask. Amount 200, Radius 1, Threshold 10

- Using the Opacity slider, fine tune the blending of the treated and untreated layers

- Save as a .psd file. Flatten image and save as a jpeg.

See my work at http://www.pbase.com/davidhobbs